Soon after Cardinal Jorge Mario Bergoglio was elected pope on March 13, 2013 — becoming not only the first ever pontiff from the Global South, but also the first Jesuit to assume the role — Jesuit Fr. Federico Lombardi, then the Vatican spokesman, told reporters he was « shocked. »

« Jesuits resist being named bishop or cardinal. To be named pope — wow, » Lombardi said. « Jesuits think of themselves as servants, not authorities in church. »

Bergoglio, who took the name of Francis upon his election, recently admitted to his fellow Jesuits in the Democratic Republic of Congo that he had twice declined being made a bishop, before eventually relenting in May 1992 to become auxiliary bishop of Buenos Aires, Argentina.

But despite the fact that Jesuits, including Bergoglio, have historically shied away from roles of authority in the Catholic Church, over the last 10 years, Francis has increasingly turned to his Jesuit confreres to take on key positions during his decadelong papacy.

‘Francis has made so many people feel at home, welcomed and sent on mission. That goes for us Jesuits, too.’

—Jesuit Fr. John Dardis

Among the Jesuits tapped for major Vatican roles are:

- Cardinal Michael Czerny, prefect of the Vatican’s Dicastery for Integral Human Development (2021-present);

- Cardinal Luis Francisco Ladaria, prefect of the Vatican’s Dicastery for the Doctrine of the Faith (2017-present);

- Cardinal Jean-Claude Hollerich, archbishop of Luxembourg since 2011, elevated to the rank of cardinal by Francis in 2019 and named relator general of the Synod of Bishops (2021-present);

- Cardinal Gianfranco Ghirlanda, former rector of the Pontifical Gregorian University and drafter of the Vatican’s new constitution, Praedicate Evangelium (2022);

- Fr. Juan Antonio Guerrero Alves, prefect of the Vatican’s Secretariat for the Economy (2020-2022).

Francis has relied on the Czechoslovakian-born Canadian Czerny to reform and run the Vatican’s mega-department that oversees the church’s global peace and justice initiatives. With Ladaria, the pope entrusted the Spanish Jesuit to pivot the Vatican’s once all-powerful doctrinal office away from its centurieslong reputation for scrutinizing theologians.

In Hollerich, the pope has placed the responsibility of drafting the eventual outcome document for the church’s ongoing synod process — a signature project of the Francis papacy, meant to return the church to embracing the Second Vatican Council’s call to listen to all of the church’s members.

Ghirlanda, one of the church’s top canon law experts, has been the architect of a number of the pope’s constitutional reforms, which allow for greater lay leadership at the Vatican and beyond. And the pope deputized Guerrero with the unenviable task of managing Vatican budgets and making its financial dealings more transparent.

Elsewhere, both in Rome and around the world, Francis is relying on fellow Jesuits to oversee key elements of his agenda.

Italian Jesuit Fr. Giacomo Costa currently serves as a consultant to the General Secretariat of the Synod, and German Jesuit Fr. Hans Zollner, director of the Institute of Anthropology at the Pontifical Gregorian University in Rome, was a lead organizer of Francis’ 2019 Vatican summit on clergy sex abuse.

In 2018, Francis elevated Peruvian Jesuit Pedro Ricardo Barreto Jimeno, archbishop of Huancayo, to the rank of cardinal. Barreto is currently the head of the Pan-Amazonian Ecclesial Network, the vast umbrella organization representing thousands of groups in the nine countries in the Amazon region.

And in 2021, when it came time to name a new bishop to assume the politically delicate posting in Hong Kong, Francis chose fellow Jesuit Stephen Chow.

Turning to the Jesuits for help

The Society of Jesus, commonly known as the Jesuits, was founded by St. Ignatius of Loyola in 1534. Although Jesuits pledge not to seek a higher office, they also take a vow of loyalty to the pope.

Veteran Vatican analyst Jesuit Fr. Thomas Reese offered a blunt assessment of Francis’ reliance on members of their shared religious order: « I never like it when a Jesuit is named bishop. »

But Reese told NCR that he had to admit that Francis’ picks have « been good for the church, » even if they may have removed some of « the best guys » from the order, since once tapped for higher office they are no longer under obedience to any Jesuit superior.

St. Ignatius, according to Reese, opposed Jesuits being made bishops for two primary reasons. First, he feared that the then-nascent religious order would be diminished when some of their most skillful members were stripped away and made bishops. Secondly, at the time, such positions were the equivalent of being princes or nobles, and Ignatius wanted Jesuits to live a simple lifestyle.

Reese believes that one of the reasons Francis has turned to Jesuits so frequently over the past 10 years is that top cardinals have not helped with recruitment by identifying like-minded priests and bishops who share in his pastoral agenda.

« So, he turns to Jesuits for help, » Reese observed.

For many Jesuits, having a member of their religious order elected pope was a bit of whiplash, given both the order’s recent history in Rome, as well as Bergoglio’s own history with the order.

Bergoglio first joined the Jesuits in the 1950s and was ordained in 1969. Less than five years later, in 1973, at the young age of 36, he was named the head of the order in Argentina and Uruguay.

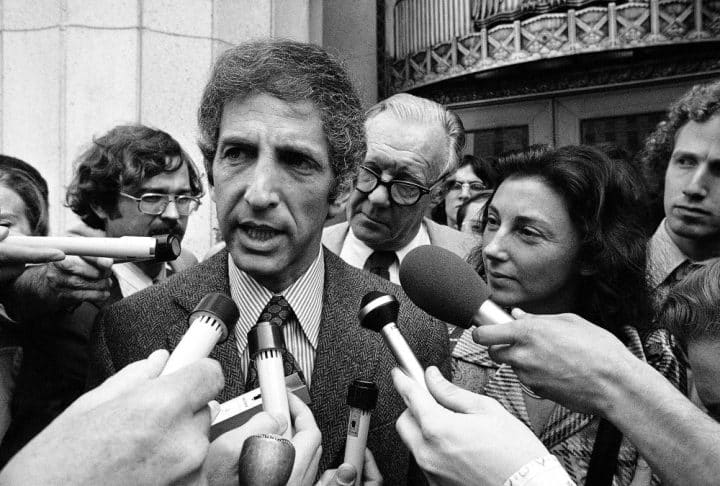

It was a tumultuous time for both the church and Argentina, as his leadership coincided with the country’s « dirty wars » — a period in which the military dictatorship hunted down anyone it believed to be associated with left-wing or socialist movements.

Bergoglio’s leadership as provincial superior polarized the Jesuits, with many resenting him for what they viewed as a crackdown on progressives in order to appease the government, leading to his eventual exile from the order.

« That was crazy. I had to deal with difficult situations, and I made my decisions abruptly and by myself, » Francis said in a 2013 interview, reflecting on those years. « My authoritarian and quick manner of making decisions led me to have serious problems and to be accused of being ultraconservative. »

Advertisement

Meanwhile, in Rome, the Jesuits were largely viewed with suspicion by Pope John Paul II, who in the early 1980s named his own delegate for the order and halted its plans to hold a general congregation and to elect a new superior. This wariness was also shared by Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, whom the Polish pope named to head the Vatican’s doctrinal office, which cracked down on a number of Jesuits.

Many Jesuits were circumspect when Bergoglio was elected pope, fearing that he might govern as a hardline disciplinarian. It hadn’t helped that in the intervening years after being made a bishop, when he traveled to Rome he chose to stay not with the Jesuits but at a guesthouse for priests.

But over the last 10 years, many Jesuits now say the Ignatian DNA of this papacy is undeniable, not just in Francis’ spirituality, but also in his approach to church governance.

Francis ‘helped us find our voice again’

Exactly one month after his election as pope, Francis established a new body of cardinals from around the world that over the last decade have met in Rome almost quarterly to advise him on key issues facing the church.

For Irish Jesuit historian Fr. Fergus O’Donoghue, Francis was taking a page right out of the Jesuit playbook.

« In our tradition, we have consultors, » he told NCR. « Every provincial has to have them and every father general has them. »

Reese concurred, adding, « Having been a provincial and studying the constitutions of the Jesuits, Francis understands well what Jesuits call ‘representation.’ «

« You can come to the superior and say, ‘I think this is wrong,’ or ‘I think we ought to do this,’ or the Jesuit superior can ask for advice, consultation or debate, » said Reese, « but ultimately it all comes to his desk and he’s going to make a decision. »

For Reese, this is something both conservatives and progressives in the church often get wrong in understanding Francis.

« He is inviting input, he is inviting discussion, but ultimately he is going to decide, » Reese said.

Fr. Arturo Sosa, the present superior general of the Society of Jesus, told NCR via email that Francis’ « insistence on the discernment of spirits as the basis for decisions in the Christian community » is one of the most obvious ways in which Francis’ leadership has relied on Ignatian spirituality.

Sosa also pointed to Francis’ evident « joy, » saying it is « a clear sign of a spirituality that asks for consolation in the relationship with the Lord and lives with it. »

Jesuit Fr. Thomas Massaro, a professor of theology at Fordham University, also said that in his view, the Jesuit charism of discernment has « really stuck with Francis. » Massaro noted that it is especially obvious in the way the pope has reinvigorated the synod process.

In both 2014 and 2015, Francis called a synod on the family, establishing a discernment period of two years to examine hot-button topics on sex and married life.

« He deliberately said we can’t do the work of discernment in one year, » Massaro told NCR. « And he’s doing it again now with the current synod [on synodality], where he’s established a worldwide discernment process. »

Jesuit Fr. Antonio Spadaro, editor of the influential Jesuit-run journal La Civiltà Cattolica and a close collaborator with Francis, recalled that the pope repeatedly expresses his gratitude for the formation he received from Jesuit Fr. Miguel Ángel Fiorito, focused especially on the role of discernment.

« The government of Francis is a government that is based on the main point of Ignatian spirituality, that of discernment, » Spadaro told NCR.

The pope, said Spadaro, tries to carefully understand « how God is at work » both in history and the lives of men and women today, allowing him to be flexible and listen to others before giving answers and making decisions. This, Spadaro added, has a mystical dimension but allows for concrete, pragmatic reforms.

Massaro, author of Mercy in Action: The Social Teachings of Pope Francis, also pointed to Francis’ emphasis on peacemaking as being directly traced to one of the Jesuit ministries recommended by St. Ignatius.

« There’s a long history of Jesuits doing that, and I see Francis as being the reconciler, arbitrator par excellence, » said Massaro, citing the pope’s direct intervention in conflict areas such as Colombia, the Central African Republic and South Sudan.

One year into his papacy, when Francis decided to fast-track the canonization process for one of his favorite Jesuits, Blessed Peter Faber, and have him named a saint, Massaro worried that Francis might be accused of showing favoritism to his brother Jesuits.

Those concerns also were voiced by others when the popular Slovenian Jesuit artist Fr. Marko Ivan Rupnik, known to have been friendly with Francis, was restricted from ministry last year after accusations that he had abused adult women. When the Rupnik scandal erupted, it was revealed that the Vatican’s doctrinal office, which is led by another Jesuit, Ladaria, had declined to prosecute the latest known case against Rupnik, stating it was past the statute of limitations.

Francis, however, has denied that the Slovenian Jesuit has received any special treatment from him and vowed that the ongoing case will adhere to the church’s legal process.

Reflecting on the 10-year anniversary of a Jesuit pope, Jesuit Fr. John Dardis observed that not only has the election left an Ignatian imprint on the Catholic Church, but it’s also left its mark on the order itself.

After the uncertain years of the 1970s and 1980s for the order, « having a Jesuit pope who uses Ignatian language helped us to find our voice again, » said Dardis, who serves as general counselor for discernment and apostolic planning at the Jesuit headquarters in Rome.

When Pope Benedict XVI addressed the members of the Jesuit’s 35th general congregation in 2008, he told those gathered to be on the frontiers of society.

« I remember how much it moved me and gave me energy. I felt we were being encouraged and affirmed, » Dardis recalled. « Pope Francis took us a step further. Francis has made so many people feel at home, welcomed and sent on mission. That goes for us Jesuits, too. »

As for the Jesuit pope himself, flying back from Canada last July, a reporter asked Francis to what extent, as pope, he still feels as if he maintains his Jesuit roots.

« The Jesuit tries to — he tries, he doesn’t always, he can’t — do the Lord’s will, » Francis acknowledged. « The Jesuit pope must do the same. »