Many people think they know the story of the hymn, »Amazing Grace. » The commonly accepted narrative presents its composer, John Newton, a young English captain of a late 18th-century slave ship, as a man who underwent a dramatic conversion after surviving a storm at sea. It was this harrowing experience, the story goes, that led him to leave the slave trade and become a pastor and abolitionist. « Amazing Grace, » we’re told, was written in 1772 in thanksgiving for Newton’s conversion from his horrific profession. It went on to become a hymn of hope for enslaved Black people and their descendants, eventually becoming beloved around the world.

The truth, as we learn in James Walvin’s book Amazing Grace: A Cultural History of the Beloved Hymn, is far more complex.

Amazing Grace : A Cultural History of the Beloved Hymn

James Walvin

216 pages; University of California Press

$19.95

Walvin’s study analyzes the history and cultural significance of this beloved hymn, from its composition to the present. The book attempts to provide a historical explanation for the overwhelming international popularity of the song, beginning with the puzzling, contradictory life of its composer and the earliest uses of the song. Drawing from a broad swath of sources, including published sheet music and personal diaries, Walvin’s book is a testament to his excellence as a historian and his thoughtful engagement with the impact and meaning of history for our time.

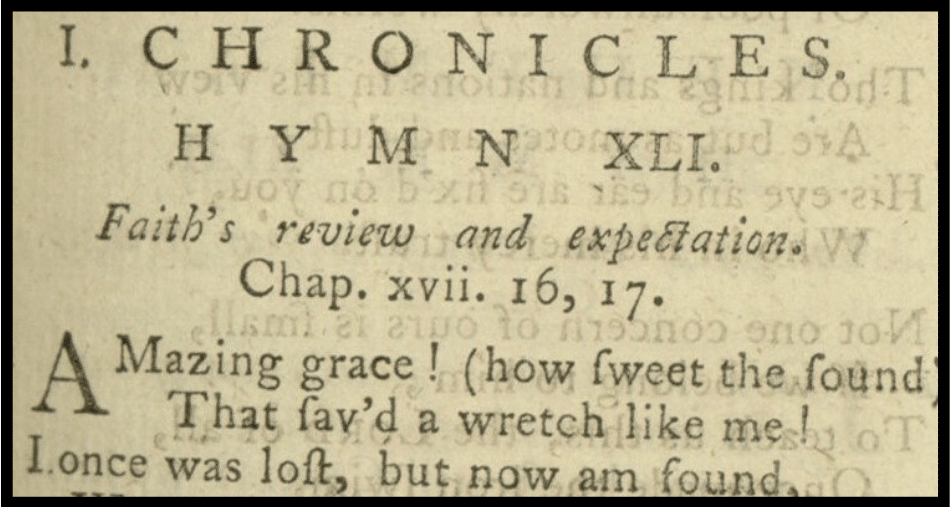

The book begins by introducing the nuances of Newton’s life and ministry, and his motivations behind the Olney Hymns, a collection published in 1779 that included « Amazing Grace. » Walvin does not skirt the uncomfortable contradictions in the story, acknowledging that Newton’s behavior as a slave ship captain was a participation in great evil and at odds with his Christian faith. Yet Walvin also describes Newton’s eventual participation in the English abolitionist movement as « almost living proof » of the lines of his own hymns. In addressing the challenging parts of Newton’s life story, Walvin speaks both to the power of « Amazing Grace » and, as Catholic tradition teaches, the transformative power of grace as one cooperates more and more fully with God’s work in one’s life.

Wavin goes on to relate how « Amazing Grace, » a relatively unknown English hymn, grew popular in America, particularly during the Great Awakenings in the 18th and 19th centuries. He notes that America had a robust popular musical culture, credited partly to its ethnic and cultural diversity, which was particularly suited for a simple, engaging song like « Amazing Grace. »

The book continues by examining the importance of the hymn to Black Americans, tracing its publishing history and persistent importance in the cultural landscape of the United States. « Amazing Grace, » Walvin writes, has been adopted as an American anthem, functioning as a symbol of the culture and an expression of American cultural identity. It connotes a plaintive hope and gratitude, regardless of religious profession.

Walvin argues that the cultural significance of « Amazing Grace » led to its particular prominence in the civil rights and antiwar movements in the 1960s and ’70s. His discussion of the commercial success of the song during that period leads into his analysis of why the social and technological changes of that particular moment in history allowed the hymn to become an international hit. Subsequent chapters discuss how the hymn became a universal human expression of hope and unity in key international events, such as 9/11 and the COVID-19 pandemic.

« Amazing Grace » expresses Black joy: a joy of knowing God’s immanent love, which provides solace and succor from the death and destruction that white supremacy attempts to perpetuate.

Walvin closes by making a striking contrast between a crowd of rioters attempting to sing « Amazing Grace » during the Jan. 6, 2021, invasion of the U.S. Capitol Building and the powerful moment in which President Barack Obama led the crowd of mourners in a rendition of the song after the mass shooting at Mother Emmanuel AME Church in Charleston, South Carolina, in 2015. Though British himself, Walvin manages to speak to the heart of the contradiction of these two American incidents. In both cases, he argues, the crowds were using a cultural symbol to express American identity. Yet, as we look at which incident resonates with the message of John Newton’s lyrics, a clear contrast emerges between the intention of its use.

One area where the book leaves the reader wanting is in its discussion of the religious meaning of the hymn. Walvin acknowledges that he has not been a practicing Christian since his teenage years, so one can hardly fault his lack of theological analysis. He is an historian whose book serves as an excellent examination of the historical and cultural significance of the hymn.

Advertisement

Yet as a Catholic reader, the discussion of the power of « Amazing Grace » to communicate hope misses the inherent contradiction of Christian hope beyond a shared human optimism. The audacity of Christian hope is not simply a belief that things will turn out right, but an affirmation of faith in God at the bleakest of moments with no guarantee of change. It is a mirror of the disciples who stood at the foot of the cross as Jesus died, knowing that they needed to be near the Lord even as it seemed all was lost. The power of « Amazing Grace » lies in its ability to communicate the unexpected joy that arises when one realizes that grace, undeserved as it may be, has turned the despair of the crucifixion into the joy of the resurrection. Grace is precious, as the lyrics say, because through Jesus, God turns the world on its head.

Because Walvin’s historical survey does not include the deeper connection to the Christian story, the reader also misses out on some of the cultural significance of the hymn for Black Americans. « Amazing Grace » holds a special place in Black churches specifically because to be black in the United States has always required the boldness that believes God can and will triumph over the many forms of oppression which racism has taken. In Jesus of Nazareth, Black Christians find the solidarity of God who knows what it means to lose everything to powers and principalities. « Amazing Grace » expresses Black joy: a joy of knowing God’s immanent love, which provides solace and succor from the death and destruction that white supremacy attempts to perpetuate.

In spite of these minor limitations, Walvin gives us a meaningful survey of a beloved hymn that is well worth the reader’s time. It would be of interest especially for those curious about the confluence of history, social change and religion. Easily accessible for those outside academia, Amazing Grace delivers an insightful look at the perennial appeal of a cherished classic.