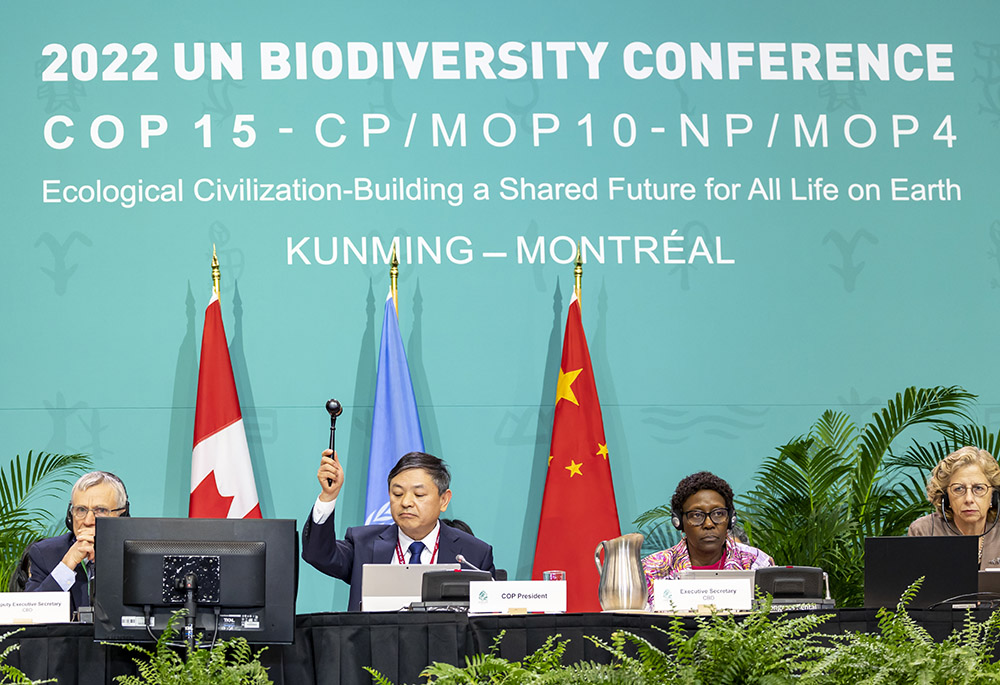

The nations of the world secured a historic deal on behalf of nature on the final day of the United Nations biodiversity summit, charting a path for the next eight years to undo decades of ecosystem destruction and species diminishment and to ensure creation’s restoration by midcentury.

A key part of the global pact aims to halt and reverse the rapid loss of biodiversity by 2030, and in that span, set aside 30% of the world’s lands, oceans and waters for ecological conservation. Such moves are viewed as critical not just to stave off rapidly accelerating rates of species extinction but also vital to international efforts to limit the impacts of climate change.

A coalition of faith-based organizations expressed great hope for the adoption of the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework reached among 195 countries in the early hours of Dec. 19 at the COP15 U.N. biodiversity conference held here in Montreal.

« It is a deal that has the potential for really transformative action, » said Alexandra Goossens-Ishii, policy lead for the Faiths at COP15 coalition and program coordinator for climate and environment advocacy for Soka Gakkai, a Buddhist organization.

« There’s a lot of good elements to it. Human rights. Earth rights. … I think a lot of what we had hoped for is in there, » Amy Echeverria, international coordinator for justice, peace and integrity of creation with the Missionary Society of St. Columban, told EarthBeat.

The Kunming-Montreal Agreement comes at a critical time for nature, with as many as 1 million species at risk of extinction by the end of the century. Decades of destructive ecosystems have left many biologically critical areas approaching dangerous, irreversible tipping points that scientists say could magnify the impacts of climate change and destabilize life on the planet.

« Great relief! » said Sacred Heart of Mary Sr. Veronica Brand. « The framework is a fruit of compromise and as such it isn’t perfect, nor is it as strong as many of us might have liked. But it offers a pathway for transformative actions in favor of life. »

‘Once biodiversity is lost, it’s lost’

The Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework lays out four central goals and 23 targets directed at restoring natural ecosystems by 2050 and constructing a world where humanity uses resources in more sustainable ways, lives in greater harmony with the rest of the created world, and reverses the damage that humans have waged on ecosystems from more than a century of overexploitation, pollution and land misuse.

Chief among the global targets is a commitment to set aside by 2030 at least 30% of the world’s lands, oceans and inland waters for conservation, with a special focus on ecologically important areas. The goal would nearly double terrestrial areas under protection now (17%), and triple such marine areas (10%), according to the U.N. Convention on Biological Diversity, which facilitated the conference and negotiations.

Environmental groups have compared the framework’s 30×30 goal to the target under the 2015 Paris Agreement on climate change to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius. Biodiversity loss and climate change are interrelated as fossil fuel extraction and deforestation exacerbate both crises, they say, so their solutions should be, too.

For instance, preserving the world’s forests, especially rainforests in the Amazon and Congo Basin, is seen as critical to protect species and absorb heat-trapping carbon emissions from the atmosphere.

The agreement also calls for countries in the next eight years to ensure at least 30% of degraded lands and waters are under restoration; bring to nearly zero the loss of important biodiversity areas; cut global food waste in half; reduce pollution risks to ecosystems from all sources, including pesticides and working to eliminate plastic pollution; and phase out or reform $500 billion annually in subsidies for activities harmful to nature.

On finance, the framework aims to close a $700 billion gap in funding for biodiversity by mobilizing by 2030 a minimum $200 billion per year for biodiversity from public and private sources, and directing at least $30 billion from developed countries to developing nations.

Advertisement

The framework also includes the first-ever reference to agroecology; notes the right to a clean, healthy and sustainable environment; and sets goals to eliminate human-induced extinction and slash extinction rates by tenfold for all species and to maintain genetic diversity.

Throughout the agreement are recognitions of the rights of Indigenous peoples and local communities to their traditional lands, a major priority in these negotiations for Native tribes and their allies, including in faith communities, who feared that new conservation efforts would push them off their territories, restrict their access to natural resources and fail to acknowledge the central role they have played in protecting biodiversity around the globe.

Hours before its adoption, the International Indigenous Forum on Biodiversity endorsed the framework, saying it included « strong language on the respect for the rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities » throughout its targets, including the 30×30 plan, and referred to their role and contribution in ecological conservation and their right to free, prior and informed consent about uses of their traditional lands.

While many of their priorities were reflected in the final framework, faith leaders said there were shortfalls, too. The final text eliminated mandatory reporting requirements for businesses. It also refers to biodiversity offsets and credits, where countries can potentially continue nature-destructive activities at home by financing conservation efforts elsewhere.

« But once biodiversity is lost, it’s lost, » Goossens-Ishii said.

Nations are expected to communicate formal national targets next year at COP16, set for 2024 in Turkey, and global progress reports are scheduled for 2026 and 2029.

Like the Paris climate accord, the Kunming-Montreal Agreement relies primarily on nations voluntarily increasing their biodiversity plans over time and global peer pressure to hold them to fulfilling their commitments.

The agreement, four years in the making and two years delayed by the COVID-19 pandemic, was not reached without last-minute controversy. The representative for the Democratic Republic of Congo objected to the proposed final text since it did not set up a specific biodiversity fund, but instead placed it under existing structures. After deliberating and a call from Mexico for the text to be adopted as is, COP15 president Huang Runqiu quickly gaveled the deal reached. Cameroon and Uganda later joined in raising issues with the procedure.

« We have in our hands a package which I think can guide us as all to work together to halt and reverse biodiversity loss, to put biodiversity on the path of recovery for the benefit of all people in the world, » said Huang, minister of ecology and environment for China, which was initially scheduled to host the conference in Kunming but could not due to the pandemic.

« Together, we take a bold step forward to protect nature, to protect the air that we breathe, the water that we drink, » said Steven Guilbeault, Canada’s environment and climate minister, calling COP15 « the most significant conference of the United Nations on biodiversity in history. »

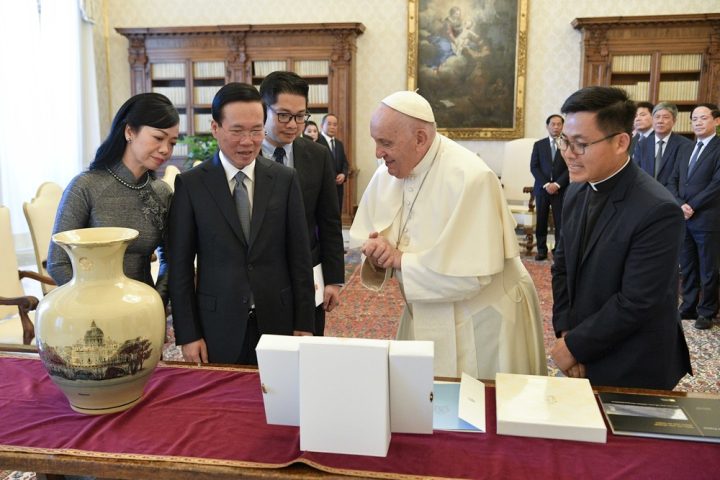

The agreement includes every nation in the world except the Holy See and the United States, which signed the convention in 1993 but has not ratified it in the U.S. Senate. Both sent delegations to Montreal, and endorsed the framework’s overall goals, including the 30×30 target.

Brand told EarthBeat that COP15’s COVID delay may have helped drive home for negotiators and others humanity’s vulnerability, « the realization that we live in a ‘common home’ sharing finite resources, and that our ‘network of life’ is seriously threatened with 1 million species at risk of extinction. »

Voices of faith at COP15

A small contingent of faith leaders were present in the plenary hall when the gavel fell and the biodiversity framework was officially adopted. They were part of the largest faith contingent present at a U.N. biodiversity conference, with approximately 40 faith leaders present in Canada representing more than 30 organizations.

The feeling in the room was a mix of joy and exuberance, shock and drama, Echeverria said.

« It felt the way you feel when you know you’ve discovered something or received something so amazing you just can’t keep it inside, » she told EarthBeat.

Gopal Patel, coordinator of Faiths for COP15, added during a recap webinar, « We’ve had about two hours of sleep last night, but we’re all very excited about the future and what this framework means for the future of our planet. »

Throughout the nearly two weeks of COP15, the Faiths at COP15 coalition sought to bring not only a moral voice but values-infused policy recommendations for country delegates to take into their negotiations.

At the faith pavilion in the Place Québec space and throughout Montreal’s multi-colored Palais des Congrès, they distributed sets of cards highlighting six thematic priorities for a global biodiversity framework, including increased ambition, addressing the drivers of biodiversity loss and utilizing a right-based approach.

More than 50 faith organizations endorsed the priorities, among them the Laudato Si’ Movement; Catholic Youth Network for Environmental Sustainability in Africa; nearly a dozen Catholic women religious congregations; and the Justice, Peace and Integrity of Creation Commission for the International Union of Superiors General and Union of Superiors General, the global umbrella leadership organizations for women religious and men religious.

Within the halls of Montreal’s downtown convention center, faith leaders held meetings with a number of U.N. officials, including Elizabeth Mrema, executive secretary of the Convention on Biological Diversity, and sought out a greater space to play a role in international environmental proceedings.

The pavilion, which was offered to Faiths at COP15 by the Convention on Biological Diversity secretariat, played host to multiple daily panels, reflecting a wide range of religious and spiritual traditions whose diverse teachings found common ground in the essential duty of humans to respect, protect and preserve their common home, the Earth. They also hosted midday peace breaks as a chance for delegates to breathe from the tense negotiations.

« There’s real interest in having our voices be present, » Echeverria said during a faith group meeting in the conference’s final days.

Looking ahead, the work of the multifaith coalition will turn to communicating the global biodiversity in their communities and what it means for them, as well as how they can act to help meet its goals — both goals shared by U.N. biodiversity executive secretary in her meeting with faith leaders.

« Let’s all read the text, understand it and share it with our communities as much as possible, » Patel said.

Excited emotions flowed through the conference hall in the hours after the framework’s adoption. The head of World Wild Fund for Nature choked up and fought back tears as he thought about what the agreement would mean for the world his grandchildren will inherit. Several faith representatives described how the feelings were similar to ones experienced in December 2015 when the Paris Agreement was adopted.

But the years since that historic accord have shown how even milestone words on paper can mean little if they’re not followed with actions, said Wesley Cocozello, communications and programs manager for the Columbans.

With both of the biodiversity agreements that preceded the Kunming-Montreal Biodiversity Global Framework, nations have failed to achieve their commitments. Faith leaders join many others in hoping this time will be different and nations will move swiftly to implement what they pledged in Montreal.

After waiting two years for COP15, the framework’s final adoption was delayed more than six hours into the late night. The exhaustion in waiting for an announcement, coming after 3 a.m., local time, reminded Echeverria of the Advent season where waiting and anticipation are also part of the process.

« It is possible; the world can come together, » she said. « Light does shine in the darkness. »