« We can rebuild him. We have the technology! »

Kids in the ’70s heard these words opening each episode of « The Six Million Dollar Man« : a show about an astronaut named Steve who, through nuclear-powered bionics implanted after a tragic accident, had superhuman strength, speed and vision. He became a secret government agent, and the bad guys always got caught.

Today’s kids don’t know the Six Million Dollar Man, but they know another superhero with extraordinary powers, thanks to science: Marvel’s Captain America, a World War II GI also named Steve who, armored with an indestructible « vibranium » shield, was transformed into a bulked-up fighting machine by an experimental « super soldier serum. »

Technologically empowered characters like Captain America and the Six Million Dollar Man have been science fiction staples for decades. They haven’t all been named Steve, and they aren’t always the good guys. I’ve watched enough « Doctor Who » to know that Cybermen are not our friends.

What has been sci-fi until now, however, is becoming reality. Active efforts with computers and chemistry aim not just to assist or even enhance humans, but ultimately to replace us with something enthusiasts insist will be better. The movement is called « transhumanism » and, according to Johns Hopkins University political philosopher Francis Fukuyama, it’s the « world’s most dangerous idea. »

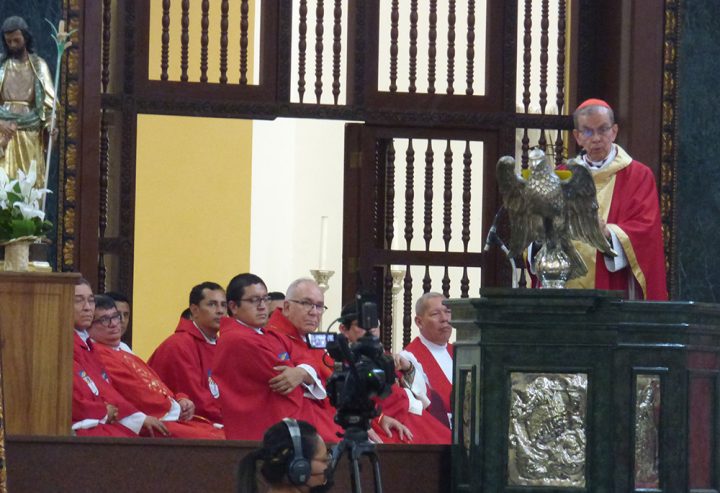

One concerned commentator has observed that « a future where the boundary between carbon-evolved and silicon-designed life becomes ever more porous is approaching at warp speed » and « will profoundly affect humanity’s future, including whether we have any. » This warning wasn’t issued at a ComicCon movie launch, the International Convention of Tinfoil Hat Conspiracists or in a dark corner of Reddit. It was made by a featured speaker at a symposium on artificial intelligence hosted by the Vatican’s then-Pontifical Council for Culture. These words understandably unsettled the audience. And reading them opened my eyes to a threat about which I’d been completely unaware.

With alarm, I proceeded to learn about the dystopian visions of tech titans like Google co-founder Larry Page, who disparages as « speciesist » those who fear humanity’s displacement by robots, and OpenAI (ChatGPT) CEO Sam Altman, who foresees an inevitable « merge » of humans and machines. Already, he blogs, « Our phones control us and tell us what to do when; social media feeds determine how we feel; search engines decide what we think. » Altman’s sometime business partner Elon Musk’s company, Neuralink, successfully (according to Musk) put an implant directly into a human brain « to redefine the boundaries of human capability. » And Musk tellingly named his youngest (and initially secret) child « Techno Mechanicus. »

Then there’s Peter Thiel, billionaire mentor to Altman and Meta/Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg, past Trump megadonor, doomsday prepper, scorner of women’s suffrage and disturbingly a primary investor in Hallow, the popular Catholic prayer app. Thiel insists that democracy and freedom are incompatible and is unconcerned with alleviating present-day poverty. Yet he’s keen to advance the transhumanist agenda, insisting that death is simply a disease to be overcome by tech. Never mind St. Paul’s insistence that Jesus already destroyed death, the « final enemy » (1 Corinthians 15:26). Thiel has other plans.

Recently, Thiel helped establish an alternative Olympics that allows doping by athletes and the use of « ergogenic aids. » Why should competitors be limited by mere human strength and skill, when that can be surpassed with tech? As « combat » will be a featured contest in these « Enhanced Games, » we can anticipate fights between wannabe Captains America and Six Million Dollar Men, replicating a popular toy from my childhood — Rock ‘Em Sock ‘Em robots — in which scowling buff bots pound each other until one’s head pops off. Vulgar entertainment on par with the recently anticipated Musk-Zuckerberg « cage match. »

Thiel could argue that new technologies already blur the line between human and machine, and bake us into computer ecosystems: goggles or headsets that warp our vision, scanners that decode our thoughts and monitor our feelings, « smart » glasses that whisper in our ears and earbuds that harvest our brainwaves. Given this and what’s on the horizon, one Washington Post cartoonist depicted the progression from computers on our desks to computers in our hands to computers on our heads to computers in our brains, threatening, as Pope Francis warns in Fratelli Tutti, to make us « prisoners of a virtual reality » who « lost the taste and flavor of the truly real. »

None of what I’ve said is meant to diminish the advances that have led to life-changing assistive devices for persons with disabilities, such as those used by Stephen Hawking, the famous cosmologist, physicist, best-selling author and longtime member of the Vatican’s Pontifical Academy of Sciences. His mechanized wheelchair and interactive computers allowed him to continue his scientific pursuits while living with ALS. He most certainly appreciated the benefits of advanced tech. At the same time, he warned that one new technology — AI — could « spell the end of the human race. »

This tragic end might come about, as Francis warns in « Laudato Si’, on Care for Our Common Home, » through a « technocracy … which sees no special value in human beings. » For if Homo sapiens are not understood as created in God’s image and possessing an inherent dignity, but dismissed as simply a transitional stepping stone to something better and more powerful, then human beings should have no more rights than a grey parrot, as transhumanist thinking suggests. And in a struggle for finite resources between humans and that which succeeds them, humans would likely lose. It’s survival of the fittest, after all.

But while human extinction may be the greatest threat posed by transhumanism, a more immediate threat is that its underlying inventions will exacerbate existing divides between the « haves » and the « have-nots. » « How wonderful it would be, » dreams Francis in Fratelli Tutti, « if the growth of scientific and technological innovation could come with more equality and social inclusion. » That would indeed be wonderful. But advanced technologies are expensive, and the rich will race to adopt them to maintain their power or simply from fear of falling behind in brutally competitive societies. After all, as Francis laments about « an economy of exclusion and inequality »: « Such an economy kills. »

Transhumanist and mega-tech investor Marc Andreessen labels « social responsibility » and « tech ethics » as « enemies » in his frightening « Techno-Optimist Manifesto. » And should such thinking prevail, we may soon find ourselves divided into « humans » and « humans plus »: a bit like the differences between premium streaming services and basic cable. The latter is still hanging on, but is quickly becoming obsolete. And, while today’s wealthy parents privilege their children with curated lives, boutique tutoring, exclusive schools, cosmetic orthodontics and now even Ozempic, such advantages in the future would be secured through robotic appendages, genetic enhancements and bodily integrated AI personal assistants — making today’s debates about equality and inclusion seem quaint.

Those without access to such technologies — or who refuse to adopt them — will be resigned to cleaning the houses of those who do. But wait — didn’t the Jetsons have a robot maid? « Rut-roh, » would say their real dog, Astro. Yet even Astro’s role may be threatened. There are plenty of robot dogs available today, including one with a flamethrower. One company makes robotic cats, available for purchase on pharmacy websites, and touts its product’s « revolutionary vibrapurr technology. » Yet my flippancy ignores the fact that such robo-felines can benefit seniors with cognitive decline through entertainment and comfort. Real benefits for real people with real needs.

Which suggests fundamental ethical questions: When do assistive technologies cross a line and become something else? When do we simply become appendages of machines, and extensions of computer systems? What does this imply about human nature, human agency, human dignity and being created in God’s image? Our faith is incarnational, and we profess belief in the « resurrection of the body, » but how will our tradition respond to bodies being replaced? Bodily « mutilations » have historically been forbidden, except for « strictly therapeutic medical reasons. » But would voluntary bionic or silicon implants be therapeutic, or not? And at what point, asks Francis in Laudato Si’, does technology become « viewed as the principal key to the meaning of existence »?

Advertisement

On captchas I smugly like to click the box that says, « I am not a robot. » But will there come a day when some might hesitate to make that claim? To borrow a disparaging tech bro metaphor for the human brain, my « meat computer » hurts to think of all this — and it breaks my already heavy heart. Which is why I’m encouraged that the Vatican takes this matter seriously, stressing the need for regulations and of technological progress that « affirms the brilliance of the human race. »

The then-Pontifical Council for Culture hosted the 2021 symposium on AI referenced earlier. The now Dicastery for Culture and Education has established a digital culture department. The Pontifical Academy of Life established the RenAIssance Foundation to fund ethical reflection on new technologies, and it issued its « Rome Call for AI Ethics, » signed by the CEO of Cisco Systems. And on Jan. 1 of this year, Francis issued his World Day of Peace message on AI and peace, warning of a « technological dictatorship. »

While the TV scientists building the Six Million Dollar Man insisted, « We have the technology! » we’ve not yet seen a truly bionic man or woman. But there are transhumanists with deep pockets (or big crypto holdings) who are working hard on it. Will they succeed in advancing that which, in Fukuyama’s words, is « the world’s most dangerous idea? » I’m not sure. Will they keep on trying? You bet. Does the church — and indeed all people of good will — need to anticipate this now through moral and social teaching? Absolutely. And posthaste.